Crime is becoming more globalized, with organized crime groups increasingly collaborating and entering into a wider range of criminal markets. As transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) grow and become more profitable, they have also become more influential. Rising global influence means that more industries are grappling with the impacts of transnational crime. As such, risks to corporations have intensified, increasingly impacting supply chains, finances and operations. To better understand this threat landscape and how companies can best protect themselves, RANE spoke with Andrej Bastar of Brasidas Group AG, Jacob Sims of Operation Shamrock, James Bosworth of Hxagon and Joshua Skule of Bow Wave LLC.

The experts RANE spoke with identified three main trends that characterize the transnational criminal ecosystem in today's world: TCOs are increasingly collaborating with each other.

Bosworth tells RANE that "because these groups are businesses, they collaborate with each other, even when they compete with each other." Sims reiterates this, pointing to a broader trend of a "confluence of multiple forms of organized crime coming together." He says, "we are noticing that network alignment is occurring." This means that major industries of crime, like the drug trade and the cybercrime market, or the drug trade and the illegal mining trade, are increasingly working together for mutual benefit. Sims offers an explanation for this phenomenon, saying that "as the supply chains and value chains of these types of crime become longer and longer, it requires a more sophisticated set of operators to run it successfully."

Sims says this means that as the drug trade and cybercrime converge, for example, the groups need not only "cultivators, mules, smuggling networks and dealers that span the entire world" to facilitate the drug trade, but also cybercrime requires personnel to recruit workers and transport them across the world, along with agents to be involved in the money laundering process for both markets. He further elaborates that "it [requires] lots of different types of specialized actors that are operating over a really wide territory. And so the number of people capable of scaling these sorts of activities is really small." Sims says that because of this, "it just makes sense that they are all starting to work together." With this increasing collaboration, Skule says that it is important to recognize "that crime is globalized more than it ever has been."

Bastar tells RANE that "especially as of early 2025," there has been "a convergence of different illicit markets, state actors and emerging technologies." He elaborates that "these different TCOs are blending trafficking, cybercrime, financial fraud and legal commercial operations." Bastar says this represents a shift, "where before they were specialized, they operate more now in a hybridized model." Bosworth notes that some groups remain highly specialized but acknowledges that many of these groups "have multiple fronts." For example, Bosworth explains that major drug traffickers are not only profiting from drug trafficking but also making a lot of money from local extortion and human trafficking, with drugs only representing a third of their business model despite being characterized as a drug cartel. Bastar explains this trend by saying that this model "enhances their profit diversification and enhances their resilience." For example, Bastar points to Balkan cartel alliances like the Kavac and Skaljari clans in Montenegro, which he says have "diversified from cocaine logistics into cyber fraud, crypto laundering and arms trafficking." Moreover, these groups use shell companies registered largely in Cyprus, the United Arab Emirates and the Netherlands "to channel both illicit proceeds and investment capital."

When asked about major trends, Sims points to the "increasing centralization of state involvement." He mentions Cambodia as a prime example of how this is occurring with human trafficking to cyber scam compounds. In September, the United States sanctioned Ly Yong Phat, a powerful Cambodian billionaire, senator and business partner to the Cambodian president, for his alleged role in trafficking forced labor to these scam centers. Referencing this case, Sims says that Cambodia is "emblematic" of growing state involvement in transnational crime, "where there is top-to-bottom state actor involvement not only in accepting bribes, but in actually perpetrating the crime and seemingly welcoming this into their country."

This growing collusion between state actors and transnational crime contributes to the growing influence and power of these groups, with Skule noting that the extremely lucrative nature of these industries leads to "actors that rival governments" in terms of money and capability. Specifically, Skule points to the growing counterintelligence capabilities, access to arms, and the influence and political status of these groups. While not perpetrated by a state actor, in a related example, Bastar speaks to organized criminal groups' growing infiltration into EU infrastructure and the criminal capture of the public procurement process. Bastar notes the growing presence of criminal groups in state-owned entities like port infrastructure, transportation, utility sectors and green energy, all of which pose legal risks for EU companies that may inadvertently become linked to criminal groups or caught up in criminal schemes.

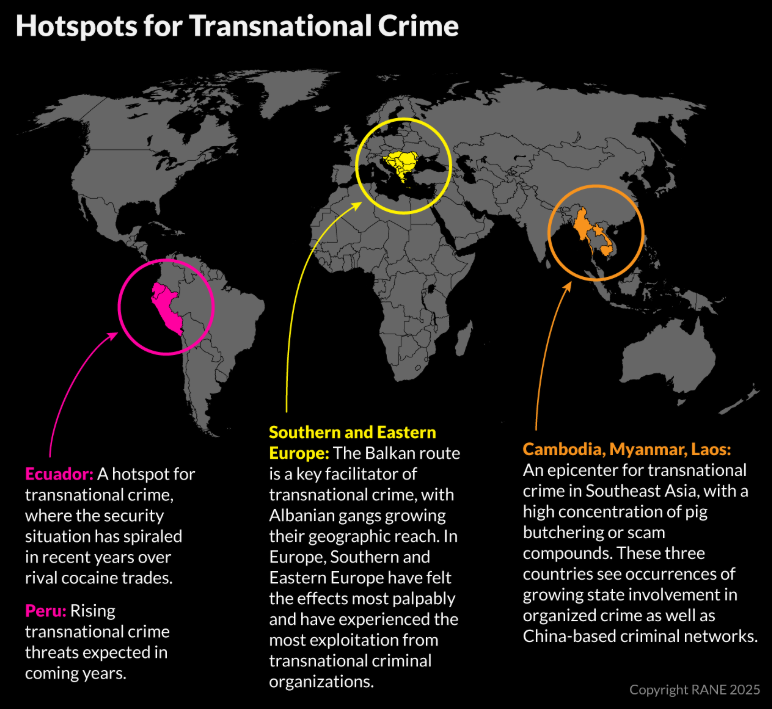

Experts told RANE that transnational crime has surged in Ecuador, Southeast Asia, and Southern and Eastern Europe. The Balkans remain a key facilitator, with Chinese organized crime groups playing an increasing role globally. Bosworth calls Ecuador a "hot spot" where "murders have tripled in the last five years" as a result of foreign, rival transnational criminal groups entering the country. He says, "it is now one of the most violent countries in the world, and it was not that way five, six years ago." To help explain this, Bosworth notes that Ecuador is not a major cocaine producer on its own, but its neighbors, Colombia and Peru, are the two main producers in the world, "so cocaine is trying to find its way out via ports." To make matters worse, he says,"Albanian gangs have entered the [cocaine] market" in Ecuador.

This means that criminal groups across the continent are coming into Ecuador and fighting over cocaine exports at the same time that Albanian groups are expanding geographically to operate in Latin America in addition to Europe. Historically, cocaine would come into the Balkans, and the Albanians would move the product around Europe. Now, however, Bosworth says that "Albanians took control of part of the supply chain that they did not control before" to get bigger profit margins, exacerbating the security situation in Ecuador and underscoring both the larger trend of how TCOs are expanding into different markets, along with the role of the Balkans as a key facilitator of transnational crime. Looking forward, Bosworth says that "Peru is the next Ecuador."

With the expansion of Albanian gangs into Latin America, the Balkans continue to act as a "critical facilitator region," as Bastar puts it, helping to enable heightened crime in Southern and Eastern Europe in particular. Bastar says that the Balkans is a "convergence point for a number of these underground economies," with a legacy of conflict and institutional corruption helping to support its role as a "transit corridor" linking Turkey and the Middle East to the European Union. Bastar says that while the Balkans are "not necessarily the source of the crime," they nonetheless see "everything from human trafficking to cocaine logistics and heroin trafficking, arms smuggling, cybercrime and money laundering." As such, coupled with government corruption, Bastar says that "the biggest issue or zone that we see is Southern Eastern Europe." Here, Bastar says that TCOs are "embedding themselves into ports and border towns across Southeast Europe, using corruption and coercion to control logistic hubs and get access to infrastructure," underscoring the broader trend of TCOs increasingly infiltrating the public sector.

Beyond Europe and Latin America, Sims says that "one of the biggest explosions of that crime in recent years has been cybercrime or transnational scams that have emerged out of Southeast Asia and predominantly concentrated within Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos." As they gain attention internationally in these areas, Sims notes that this type of criminal enterprise is popping up in other areas as well, but that Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos "are still the epicenter." These scam compounds are run largely by criminal networks originating from China and often with coordination from local criminal organizations. While Sims notes an expansion in these operations from China-based criminal networks, Bastar also highlights an uptick and growing role of Chinese organized crime groups in Europe that are engaging in counterfeit production and crypto money laundering using small and medium-sized businesses, as well as environmental crime like illegal logging, mining, wildlife trafficking, waste dumping and carbon credit frauds. Bastar says these groups' "operations intersect with the Latin American cocaine logistics and Africa smuggling routes," underscoring the increasingly globalized and interconnected nature of crime.

Bastar points to a wide array of criminal markets that have grown in recent years, including ransomware and cybercrime enabled by greater digitization, environmental crime like illegal logging, money laundering, counterfeit and fraudulent goods, and sanctions evasion or dual-use goods smuggling, which has been brought on amid geopolitical conflicts like the Russia-Ukraine war. Data from the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime echoes Bastar's insights, with the Global Organized Crime Index showing that its scores to assess criminality increased in every criminal market between 2021-23. Human smuggling and the synthetic drug trade represented the largest increases for the Global Organized Crime Index. This data underscores points from Bosworth and Skule, who both comment on a marked increase in the fentanyl and synthetic drug trade. Skule says that "for more than a decade, [there has been] a flood of fentanyl coming over from Mexico," into the United States. Bosworth notes that the shift from plant-based drugs to synthetic drugs has dramatically changed the nature of transnational crime in Latin America, with groups that were previously growing opium and heroin in Afghanistan and Mexico no longer making the same kind of profits.

Instead, Bosworth says that this has shifted with "precursor chemicals coming from places like China and India." Meanwhile, Bastar sheds light on the dual-use goods smuggling market, saying that in recent years, this industry has been highly active in bringing goods to Russia, Iran and North Korea, with Turkey, Armenia, the Emirates and others in Central Asia often used as the intermediate countries. Additionally, Bastar notes that the Balkans are typically used as a node for dual-use goods smuggling, "very often via Serbia." Bastar also points to Iranian procurement groups that are launching from Lebanon and Syria as a way of evading sanctions, with a "touch point in the Balkans," along with nodes in Germany, the Netherlands and France.

Experts cited weak rule of law, ongoing conflict and the gambling industry as major drivers of transnational crime. Bosworth says that "weak rule of law creates openings for organized crime to come in." He elaborates that it often begins with moving things across borders for profit before cascading into different types of crime. Relatedly, Bastar points towards conflict as an enabler of weak rule of law, saying that "conflict drives sanctions evasion and dual-use goods smuggling and weakened rule of law that can further enable transnational crime." Sims reiterates these thoughts, noting that Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos are epicenters of crime because they exhibit the "perfect storm" of factors like degraded rule of law, along with "large populations of vulnerable people seeking jobs." Similarly, Sims notes how gambling plays a role, saying that "the gray market of the gambling industry provides criminals with a wealth of opportunities to scale their operations." Specifically, he points to "the cash nature of the business and the easily explainable gains and losses," which "makes it ideal if you are already embedded in those networks to transfer it into illicit flows." Sims elaborates that a "24/7 cash business where no one asks questions when large amounts of money are moving in and out" makes gambling "the perfect mixer in terms of a money laundering instrument."

To think about future trends in transnational crime, Bosworth also says that "the price of gold matters." For example, "when the price of cocaine drops and the price of gold goes up, gold becomes more profitable than cocaine, and illegal mining becomes much more profitable than illegal drug trafficking." Like other drivers of transnational crime, this factor can be helpful for organizations to think about in terms of identifying areas where they may be most vulnerable to the impacts of transnational crime and for planning for a projected increase in the types of crime that impact their organizations the most or the least.

While Skule says every organization "has a risk at some point of being involved with organized criminal elements," some industries are at a higher risk than others. Bosworth says that any organization with fixed assets is at a higher risk because "when you have fixed assets, you're very vulnerable to extortion." Further explaining this phenomenon, Bosworth gives the example of mining – a highly vulnerable sector to organized crime – saying, "the mines can't move, and therefore, the group that controls the mining sector can extort that mining company." This applies not only to extractive industries, including agriculture, but also to large-scale manufacturing. Beyond this, our experts highlighted the financial sector, logistics and transportation, industrial machinery and tech exporters, and the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors as most at risk. Here is what they had to say about each of these sectors:

Speaking to the broad range of impacts transnational crime can have on organizations, Skule tells RANE, "it's business risk, it's reputational risk, it's operational risk." If implicated in criminal activity, Skule points towards broader risks resulting from reputational damage, saying that "if you take a reputational hit for engaging in poor business practices, you run the risk of folks not wanting to do business with you … which impacts your losses in a greater value [than compliance fines] because people refuse to do business with you." Companies face reputational risks not only if they are implicated in criminal activity but also if they fall victim to it, because being successfully targeted by criminal groups can suggest a failure of business processes and controls and may call into question the security of the company.

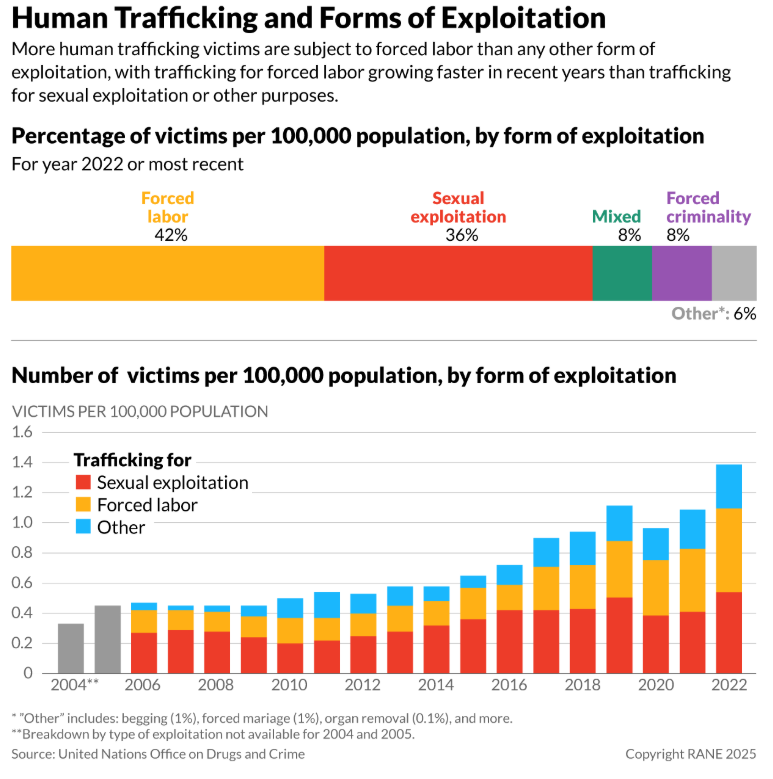

Of special note, Skule flags that one of the biggest areas of vulnerability for corporations is sourcing unskilled labor, as forced labor represents the largest form of exploitation for victims of human trafficking. Skule says this is true for both "services that are either supporting or that you are directly hiring for that are more manual labor services." He emphasizes the importance of due diligence and vetting of any service an organization uses, such as cleaning crews. In the due diligence process, Skule suggests asking of any service or third party: "What are their hiring practices? How do you guarantee that they are not trafficking for forced labor? Is the company controlled by an organized criminal element?"

To protect against the risks associated with transnational crime, our experts suggest an array of best practices for organizations to undertake. At the heart of this is information sharing. Bosworth tells RANE that "all companies should be sharing information," particularly with their neighbors. Bosworth says that "getting good intel from the local community as well as sharing information locally with their geographic neighbors" can help organizations protect against the impacts of transnational crime. Bastar also echoes the importance of information sharing, emphasizing more public-private partnerships that can help share intelligence and coordinate law enforcement efforts.

Our experts also emphasized the importance of due diligence. Skule says that "doing your due diligence on hiring practices … is critical for your supply chain." Within this process, he says, "know your vendors." Skule says global companies, in particular, "need to understand the hiring practices of partner companies to reduce risk of unintentionally becoming associated with organized criminal elements." Bastar echoes this, emphasizing due diligence and Ultimate Beneficial Ownership (UBO) screening as essential baselines; companies, particularly those operating in high-risk environments, should go beyond standard Know Your Customer (KYC) procedures. This is especially critical in sectors such as shipping, energy trading, chemicals and precious metals, where complex ownership structures and jurisdictional opacity can obscure exposure to illicit activity or sanctioned entities.

Sims provides guidance specifically for the financial sector. Sims encourages financial organizations to improve consumer fraud protections not only to ensure they are aligned from a compliance standpoint but also because, he says, "there is a clearly aligned self-interest for banks to do what they can to dissuade their customers from making bad decisions with money that they are holding." This helps to protect financial organizations from blame for customers who are victims of financial fraud or cyber scams, helping to shield the organization from reputational harm and potential legal action from the customer.

When operating in areas with high rates of transnational crime or planning for such scenarios, Bosworth tells organizations that an important exercise is to think big picture and worst-case scenario. He says, "think about the 10x or 100x exercise" and ask "what would be your worst case scenario and then make it 10x or 100x worse." This can help organizations address the systemwide security risks. Bosworth says "protecting against that mass event becomes really important because sometimes those are the big losses that actually cause problems."

Finally, Sims strongly encourages organizations to invest in rule of law initiatives. He says this not only helps organizations bolster their reputations and spend their money ethically, but it also helps to address the drivers of transnational crime at its source. Sims says that corporations working in enabling environments should consider trying "to strengthen how those governments operate or work with partners on the ground that are trying to do that." This, he says, not only "tells a nice narrative of a corporation's intent to contribute to ethical supply chains, but also has a real chance of actually impacting and changing the situation on the ground from which all these issues are emerging." He says that "all of this emerges from justice systems that don't function properly, corruption, low capacity of government to go after crimes in an effective way," and that investing in "NGOs that work in the justice system and work to combat organized crime" or funding research into these issues, as well as "funding the capacity building of local government offices," is a way for corporations to mitigate risks.

About the Experts:

Andrej Bastar is Managing Director and co-founder of Brasidas Group AG, a Swiss-based global strategic intelligence and risk advisory company that operates throughout the Middle East, Africa, Asia, Europe, Russia and Commonwealth of Independent State (CIS) countries. Andrej has over 20 years of international experience in the areas of business intelligence, investigations and analysis, having amassed a personal network of relevant contacts across multiple business and governmental segments. Prior to co-founding Brasidas, Andrej worked for the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), investigating war crimes. Andrej holds a Master of Science degree from John Jay College of Criminal Justice, focused on Forensic Science. He holds a BA from Rutgers University.

James Bosworth writes and consults on politics, security, economics and technology issues in emerging markets, primarily Latin America and the Caribbean. He is the Founder of Hxagon, a consulting company that provides political risk analysis and bespoke investigations in emerging markets on topics including election predictions, political economy outlooks and cryptocurrency usage. James, also known as Boz, is the author of the weekly newsletter, Latin America Risk Report, and has a weekly column in World Politics Review. James is a global fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center's Latin America Program and a certified Superforecaster for Good Judgement, Inc. James holds a BA in Political Science and History from Washington University, St. Louis.

Jacob Sims leads various efforts to combat human rights violations, transnational crime and address global development challenges. Jake is a Board Advisor and Executive Vice President for International Programs and Government Affairs of Operation Shamrock, a public-private coalition dedicated to disrupting transnational organized crime's expansion of human trafficking and cyber fraud crime, such as the "pig butchering" epidemic in Southeast Asia. Jake concurrently works as a columnist for The Diplomat publication, as a visiting expert on transnational crime at the U.S. Institute for Peace, and as an advisor to other organizations and government agencies, including the United Nations and the US Department of State with regard to the trafficking-transnational cybercrime nexus and other emerging non-traditional security threats. He previously served in various leadership roles with the International Justice Mission, including an in-country position in Cambodia. Jake has led policy research at the College of William and Mary and conducted human rights research in northern Myanmar. Jake holds a Master of Science (MSc) in International Development and Economic History from the London School of Economics and Political Science and a Bachelor of Science (BS) in Accounting from Grove City College.

Joshua Skule is the CEO and Founder of Bow Wave LLC. Prior to Bow Wave, Josh was Senior Vice President of Allied Universal's Risk Advisory and Consulting Services. Prior to his entry into the private sector, Josh had a 21-year career with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, including roles as Executive Assistant Director for Intelligence, leading the Bureau's Intelligence Branch. Josh is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy in 1991. Before joining the FBI, he served as a U.S. Marine Captain and led teams in challenging deployments worldwide. Bow Wave provides professional technology services for a variety of mission-critical fields to support U.S. National Security. The firm's leadership provides over 60 years of U.S. Government and commercial executive and operational leadership experience.